Stories

These interactive visualizations convey the geographic scale of the defiant girl story as a worldwide phenomenon. They are based on data sourced from 456 versions that were transcribed in over 120 languages (including creoles) between 1870 and 2020. In this series of maps visitors can explore “big picture” views of global patterns in the collection and publication of these stories, or browse information on individual transcriptions.

Overview

This interactive visualization allows visitors to explore 456 transcriptions of the defiant girl story (1870-2020). These stories were told by people of all ages and walks of life and written down by anthropologists, creative writers, linguists, priests, folklorists, colonial administrators, and politicians.

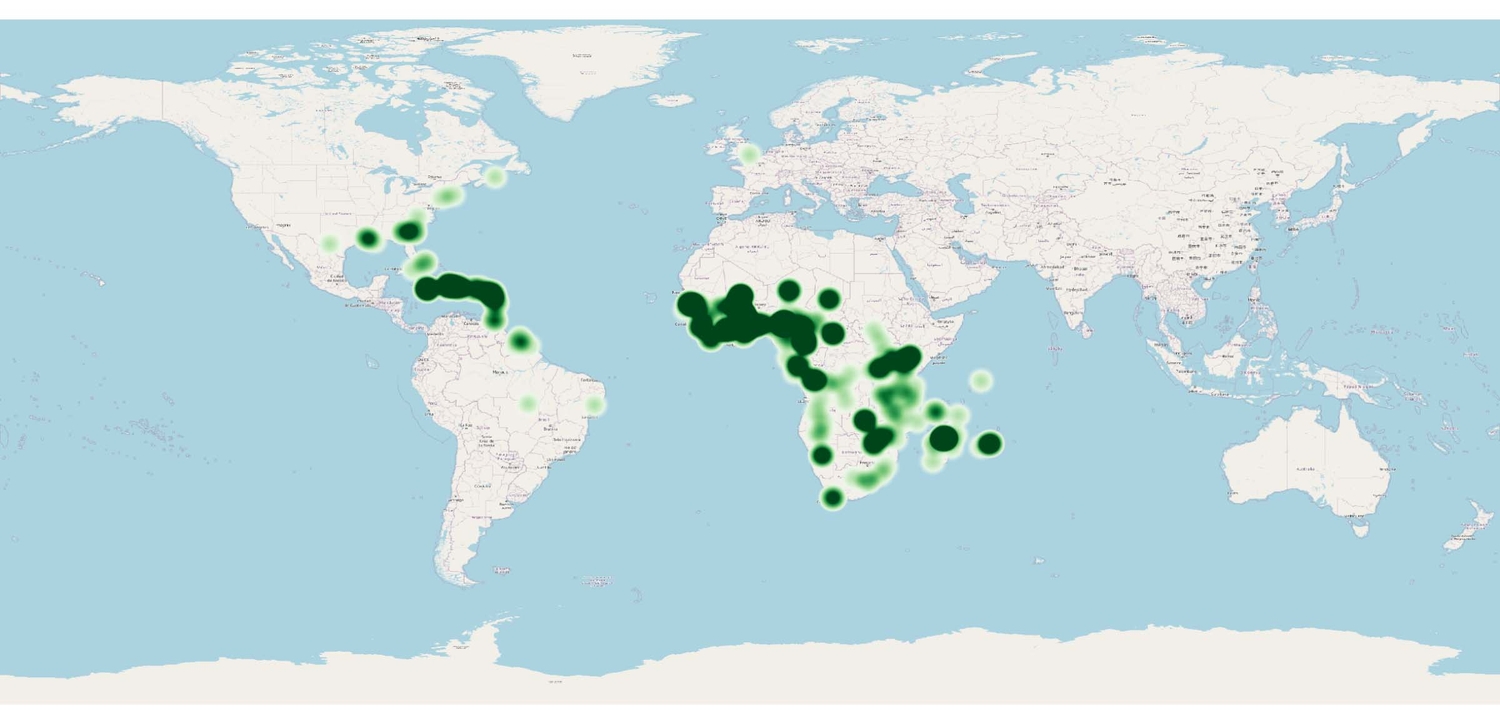

Stories Heatmap - Collection

This heatmap illustrates the geographic range of the defiant girl story as an oral narrative.

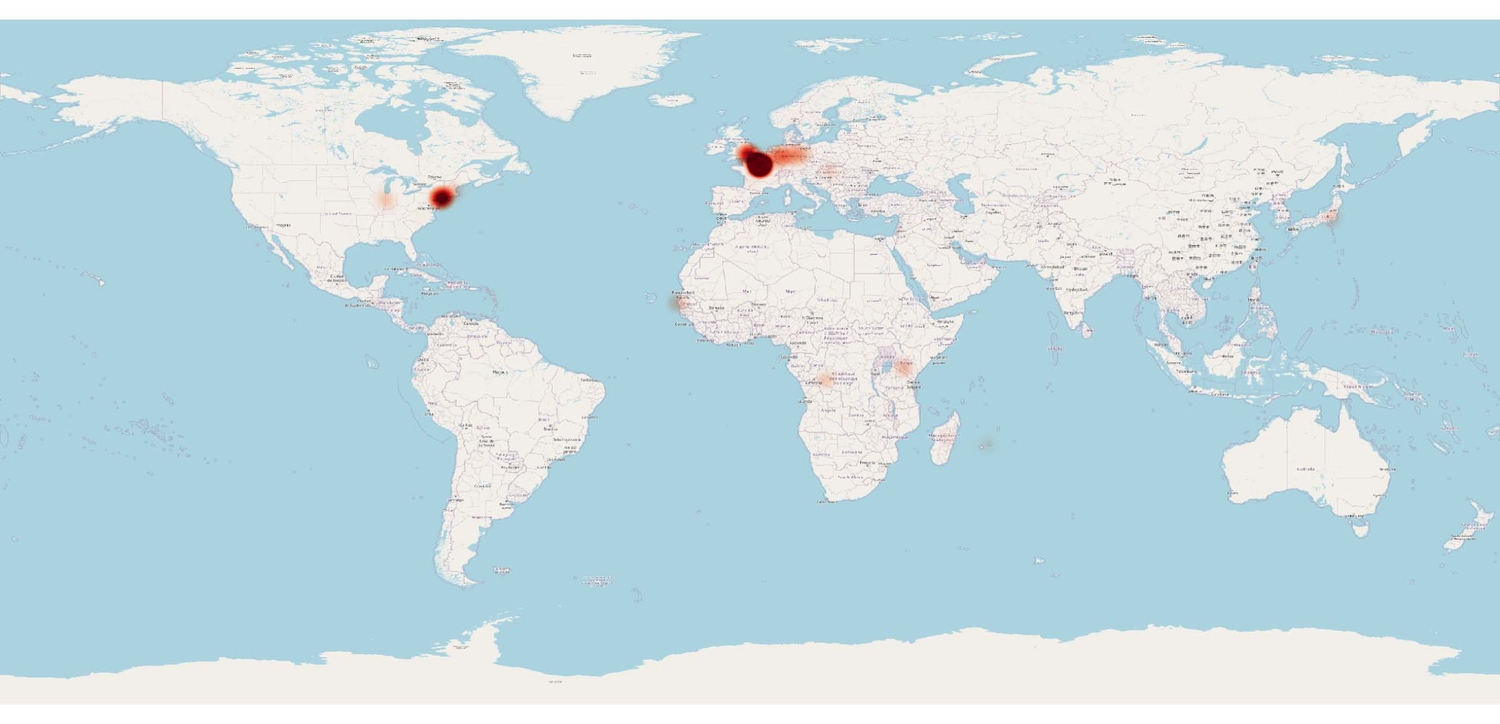

Stories Heatmap - Publication

This heatmap shows where the 456 versions collected in the previous map were copyrighted or published. The transformation is striking: with few exceptions, when these stories were transcribed and printed as folktales they tended to be copyrighted elsewhere – usually in the North Atlantic – and translated into just a handful of languages. This pattern suggests that world literature often served as an extractive economy for oral narratives collected in Africa and its diasporas.

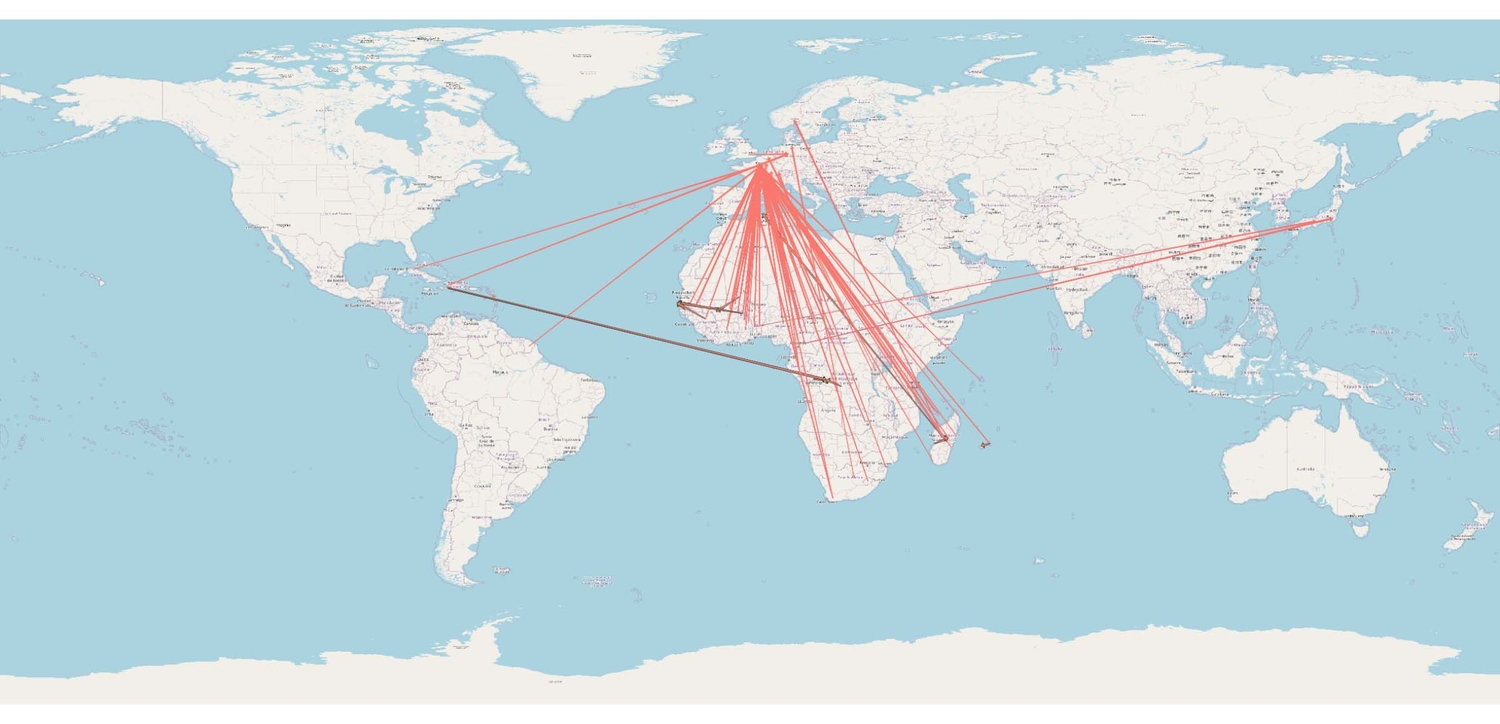

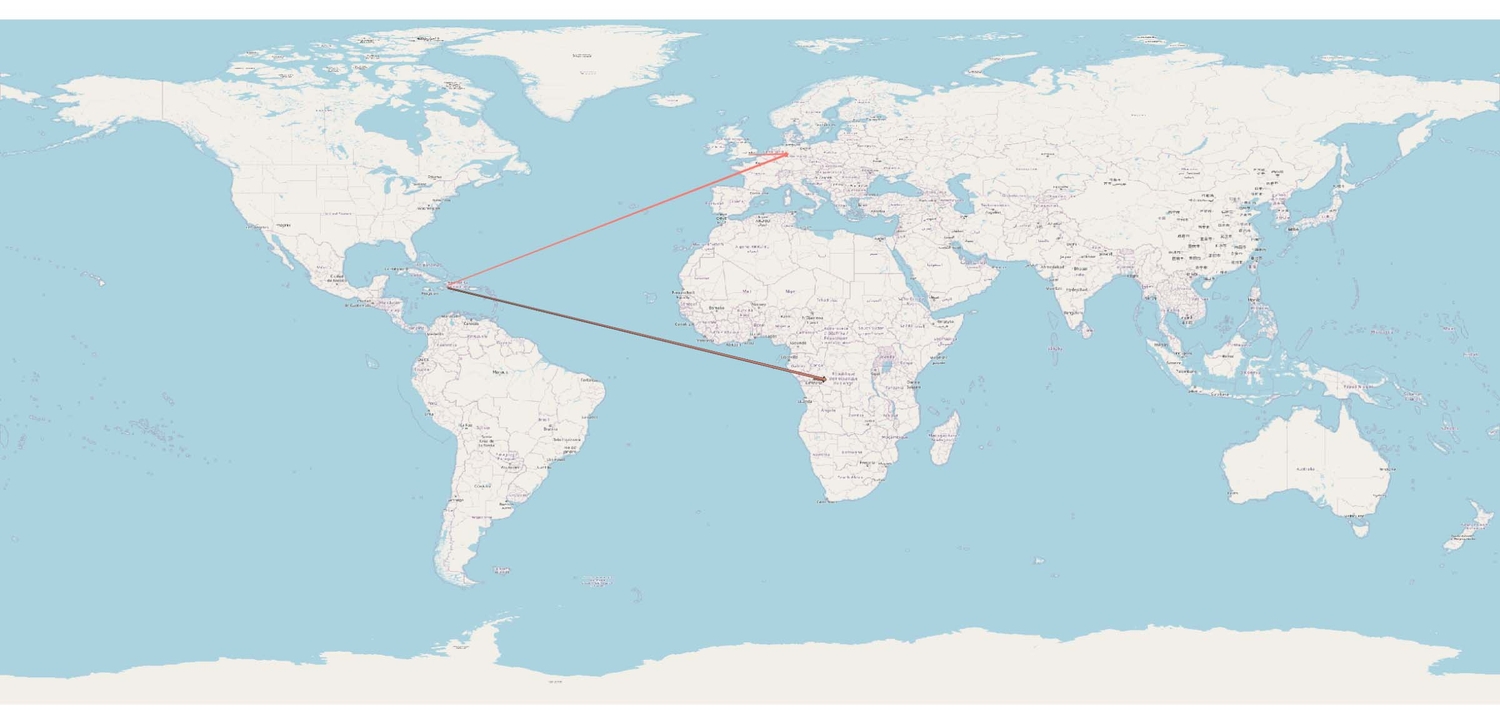

Publication Trajectories

The large-scale movement of oral narratives into printed texts can also be viewed linearly. This visualization shows the publication trajectories of all versions of the story that were printed in French. Arrows depart from the site of transcription of the story and end where the story was published, showing an accumulation in Europe, especially in Paris.

But viewing stories as trajectories can also draw out the activities of individual researchers who did not conform to larger patterns. Here are the versions collected by the Haitian anthropologist Suzanne Comhaire-Sylvain, who in published in French but worked between the Caribbean and the African continent.

Adaptations

These interactive visualizations present an overview of over 100 adaptations and translations of the defiant girl story produced over the last century by creative writers who worked in a variety of media. The tale was reworked in literary forms such as novels, poems, and short stories, as well as in more popular media such as newspapers, market literature, traveling theater, and comics. Visitors can browse individual adaptations or explore how certain influential versions spread networks of the story across dozens of languages through translation.

Overview

If the collection of the story as a folktale reveals a pattern of extraction, the many adaptations of the tale by creative writers present a more dynamic picture of circulation and reinvention. Some of these adaptations are by renowned writers, including Maryse Condé, Ngũgĩ Wa’Thiongo, Patrick Chamoiseau, Ama Ata Aidoo, Taban Lo Liyong, Efua Sutherland, Sofia Samatar, and Ahmadou Kourouma. Some are reprintings important anthologies by notable editors including Langston Hughes, Richard Rive, and Raphaël Confiant. Also included are several philosophical responses to the story’s motifs by theorists such as Achille Mbembe and Francis Nyamnjoh.

Networks of Adaptations

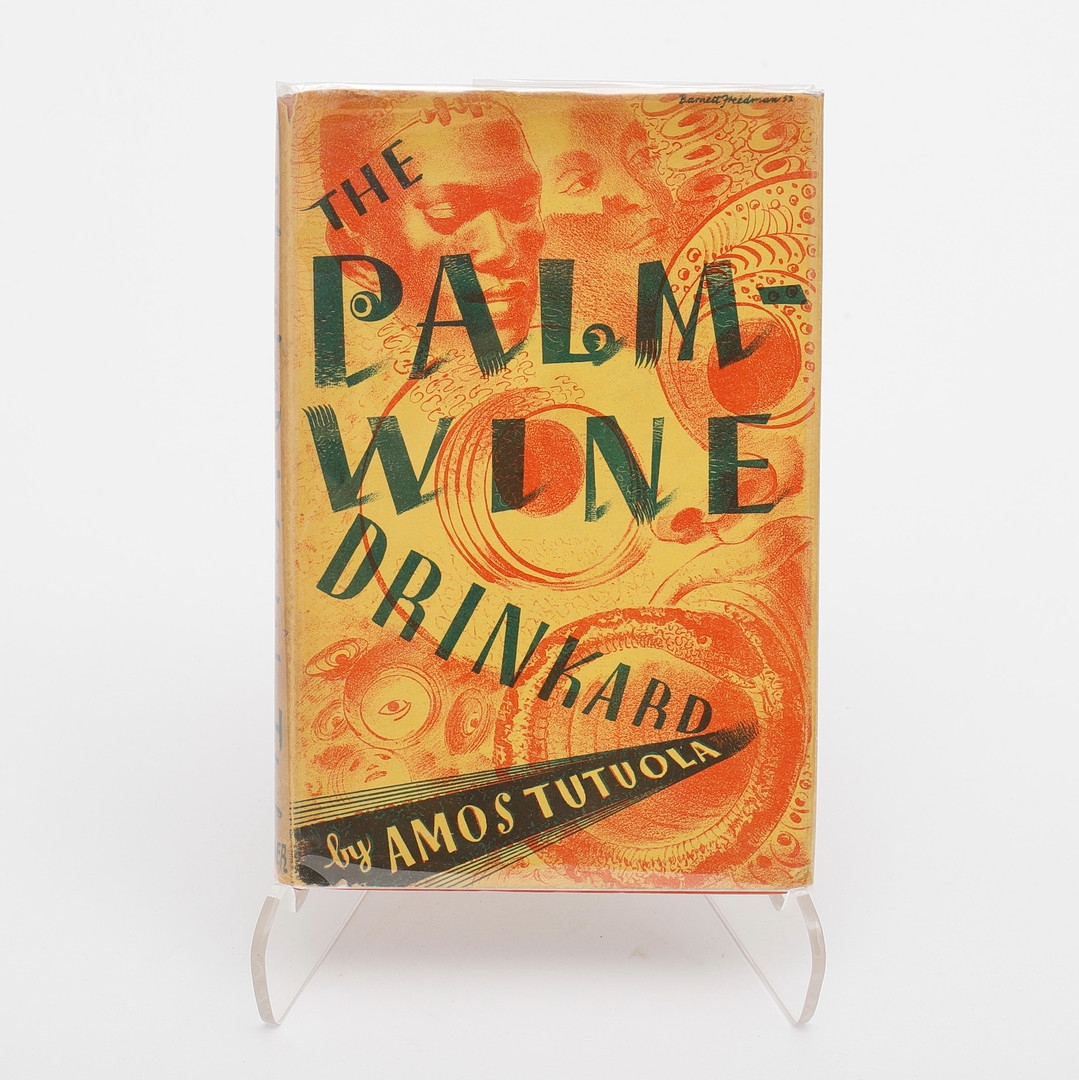

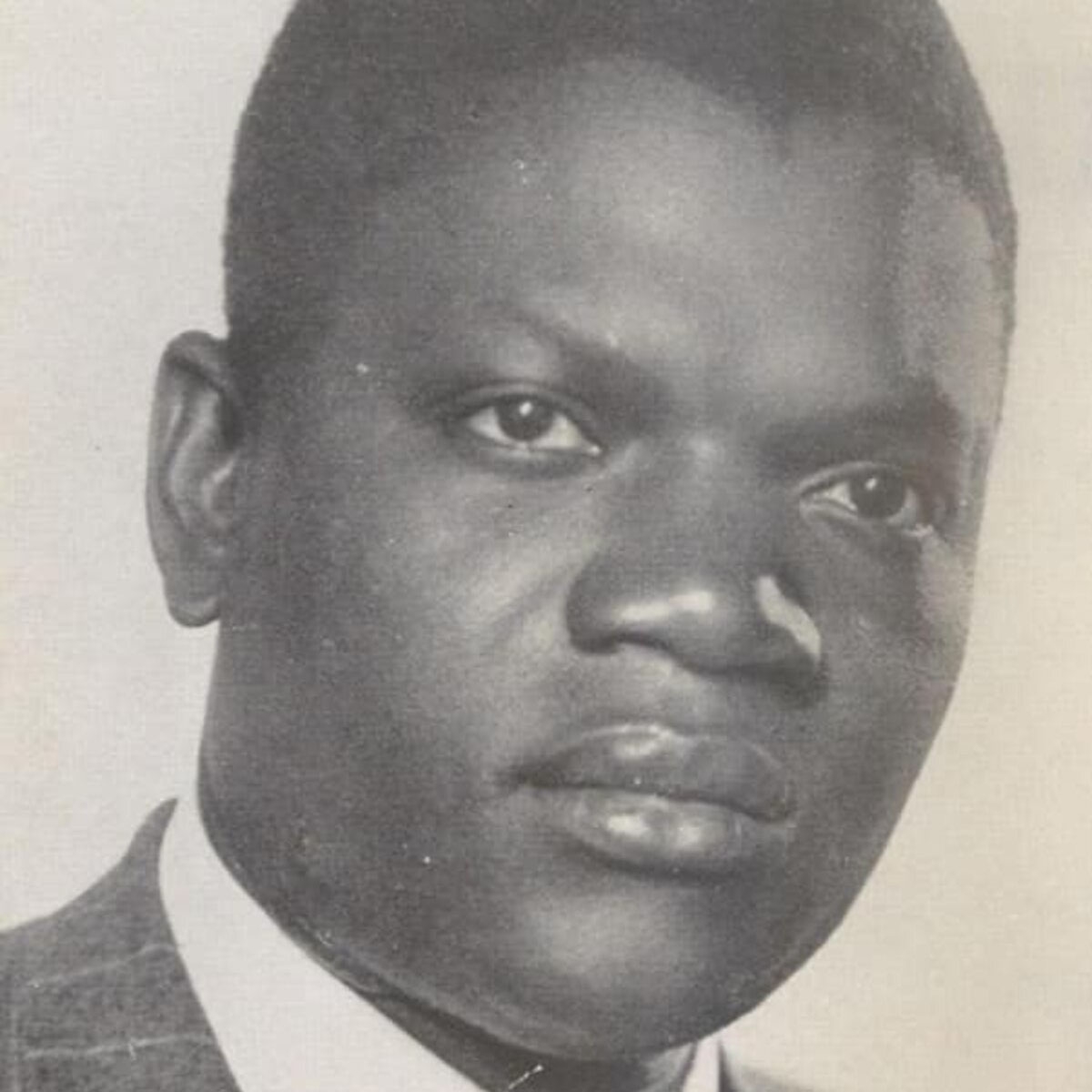

Amos Tutuola: The Palm-Wine Drinkard (1952)

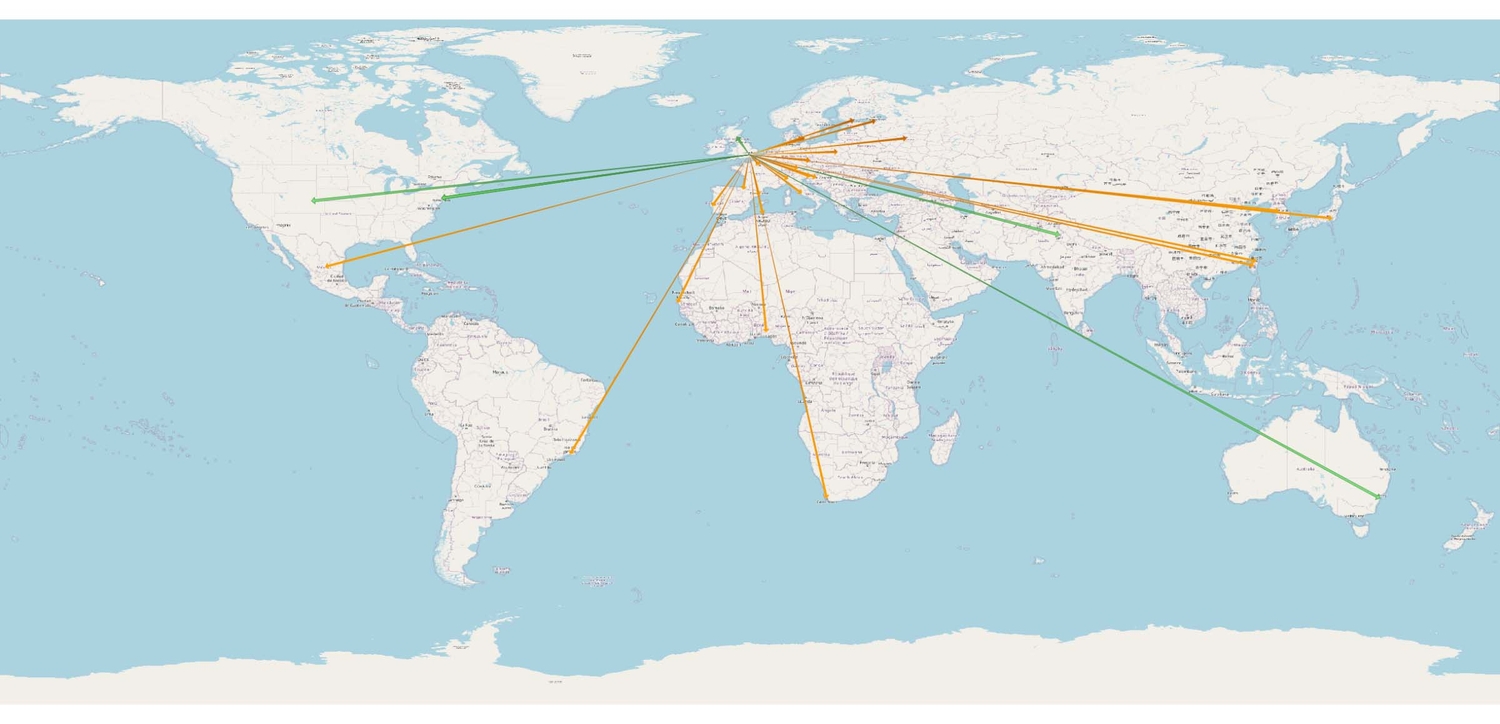

Some adaptations spread more widely than others. The most famous version to circulate in print in the twentieth century is the story of the “beautiful complete gentleman” that Amos Tutuola includes in The Palm-Wine Drinkard. Tutuola adapted Yoruba folklore into his own otherworldly adventure stories when he was a clerk in the Department of Labor in Lagos. His manuscript found its way to Faber & Faber in London who published it to great acclaim and some controversy in 1952 and has captivated audiences ever since. Tutuola’s tale of a “curious creature from the market” who assembles a body for himself out of rented parts has been translated into 25 languages, adapted for the stage and the comics page, and inspired numerous elaborations by other writers and thinkers. The colored arrows indicate diffusion through translations (orange) and anthologies (green).

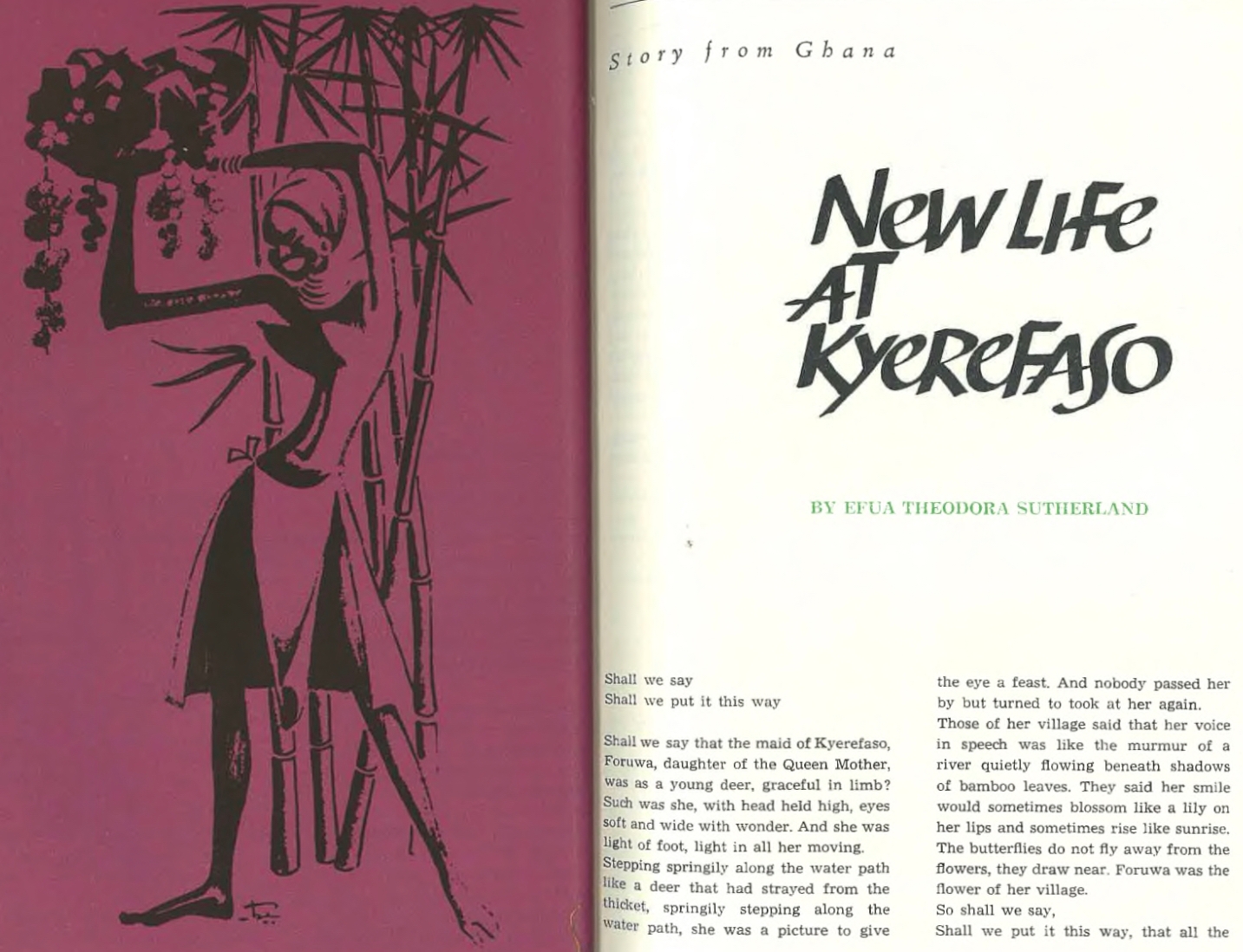

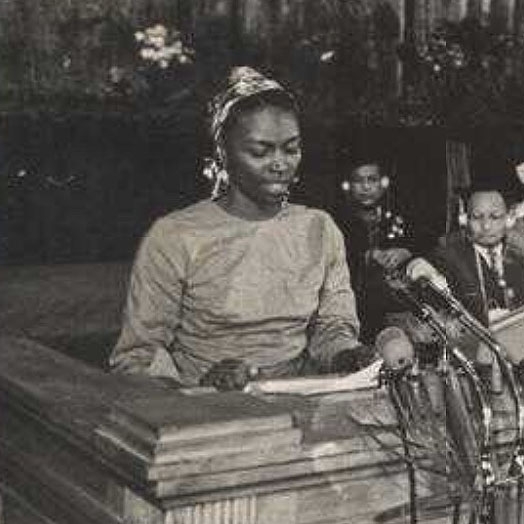

Efua Sutherland and Langston Hughes: “New Life at Kyerefaso” (1956)

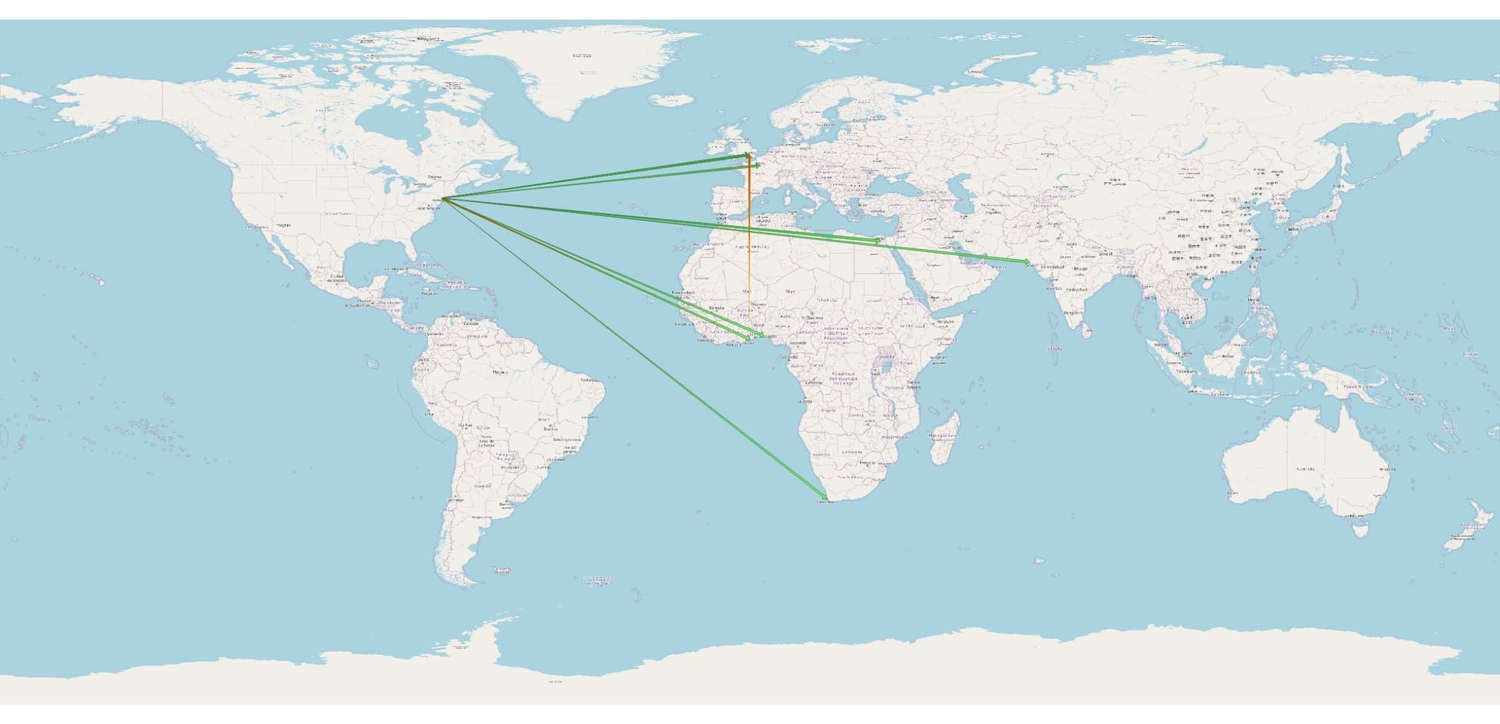

The Ghanaian playwright and poet Efua Sutherland wrote one of the most widely reprinted literary versions of the defiant girl story. “New Life at Kyerefaso” was first performed on the radio in the 1950s in what was then the Gold Coast. Sutherland next sent the story to Langston Hughes for inclusion in a 1961 collection of African writing. Sutherland’s version subtracts the terrifying creature from the equation and makes the young woman’s defiance of her community into an allegory of progress and modernization. “Kyerefaso” proved wildly popular and went on to be reprinted dozens of times across the bifurcated literary landscape of the Cold War, appearing in collections published by Heinemann as well as the Afro-Asian Writers Bureau. The different colored arrows correspond to the movement of Sutherland’s original story (orange) vs the many reprintings based on Hughes’ anthology (green).

David Diop: Frère d’âme (2018)

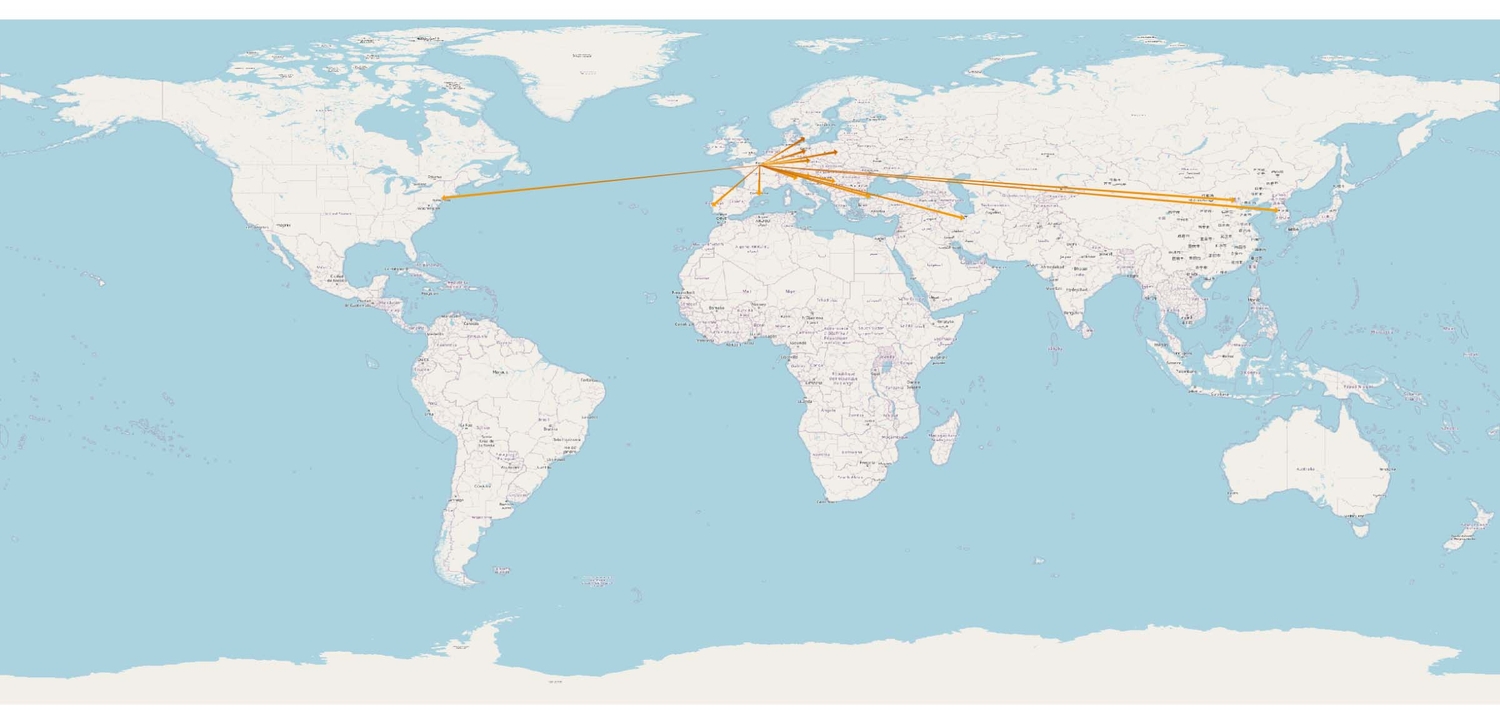

The Senegalese novelist David Diop constructed his prizewinning 2018 novel Frère d’âme around the defiant girl story. Set amongst Senegalese soldiers fighting in the trenches of World War I, Diop’s novel takes one of the tale’s common motifs – an impossible desire for a body without scars – and turns it into a probing meditation on the limits of identity and storytelling. Translated into English as At Night All Blood is Black, Diop’s book won the Man Booker Prize and has since been translated into fifteen more languages.